In conversation with Barbara Pflanzner, 2023

Let’s talk about your paintings first. In your artist statement, you describe the body as fractured form meaning to represent a situation or a memory. Can you expand on that?

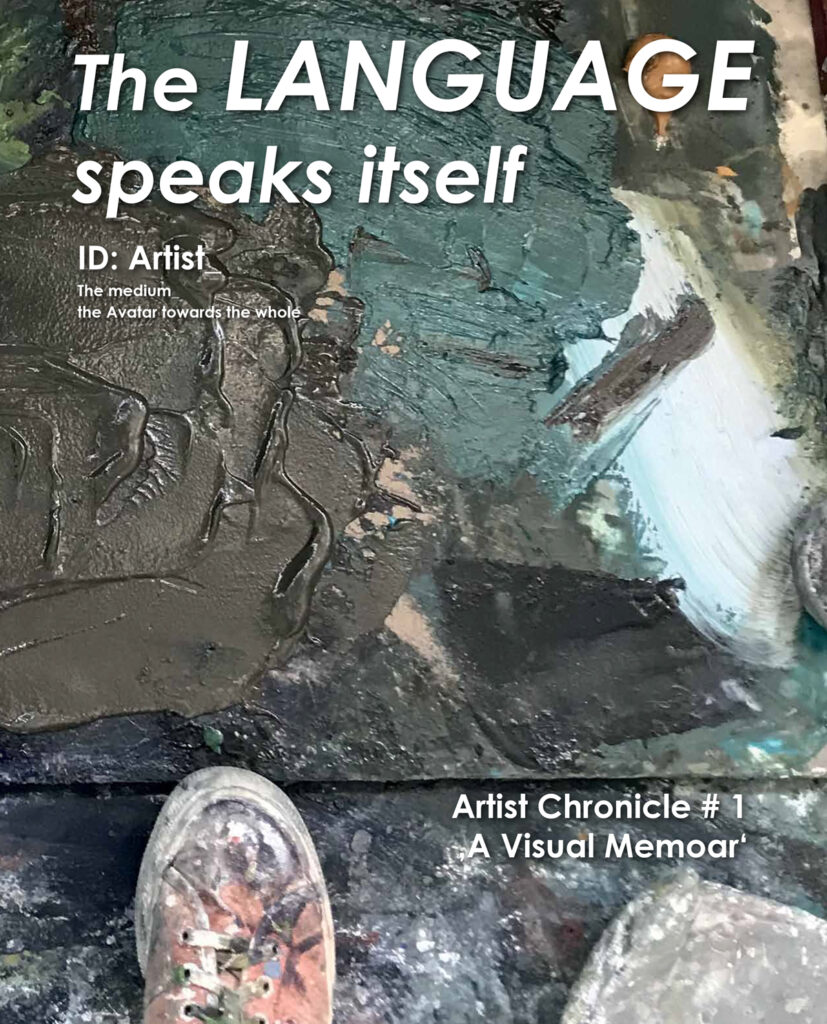

All my works relate to my own body; as well to the relationship to bodies in general. The pieces have been worked through my body several times, becoming a personal relationship. Painting is not an intellectual process for me. While working, the endless number of possibilities can be overwhelming and I find the intuitive filtering process interesting, in what I am doing through gesture. In what way my own brain start making things up and how I can trigger myself as well as the viewer to make sense of what can be seen is what faschinates me. With what I associate, feel and remember are the three rolling components as I am doing the work but in the end, the works mustn’t be personal. Finding elements which can translate into something more universal is important.

Can you tell me a bit about your way of reduction?

In the very beginning, when I started to paint, my works often lacked contrast. Only later, I gained understanding of how neccesary contrast is to my work, to create a more powerful impact. I tend to muted colors and layer the image with lighter ones, which makes them more toned or vague – it creates a blurriness. If it’s too much of that, the work doesn’t communicate as strongly as I would like. Especially within the last few years, I have improved in trying to increase the contrast in the works. By doing so, there is not just plain darkness but also very much depth within it. With abstraction, you need to know where you draw your inference from – I guess from finding the invisible aspects of the world or my own sense of being, through my working style, through my gestures. The memory of what I imagined as well as the situation I associated with when creating it and what I can see is crucial – the elements of what emerges from the unconscious is captivating, as well as the question of what I don’t show, what, in a way, I have censored and what I make of it.

Would you agree that your focus lies on a sensitive balancing of coloristic possibilities?

I agree. Colors are essential to me. Usually, I start a painting much more explosive than they eventually end up. In the beginning, they are generally wilder and often even stronger in the color schemes. As the process of balancing begins I am trying to distinguish what I can see and further build on. These kinds of invisible traces stem from the unconscious and appear in a way magically on to the surface. But seeking balance has become very important to me. When I look at my earlier paintings they were often wilder than now but also more unbalanced. It is a fine line because I like the rough aspects of the works, which I also want to maintain as much as possible. I need wildness in a balanced way, as ambiguous as that may sound. I try to paint something with both these characteristics that can simultaneously be wild and calm.

In your studio here at Creative Cluster, you are working on large-sized objects. Did you work with objects already while studying at the Academy?

I’ve always done both. The painting just requires most of my time. Working on objects needs space. If you are not working site-specifically in a show room, you need to imagine the space in which the objects should be shown, which is very tricky. Painting is different because a two-dimensional work only requires a wall. Working here in the studio space has been very good. I am really grateful for this

opportunity to work on these new objects. Because the paintings are stored somewhere else, it is the first time I can keep the two media separate and focus on the objects only.

What is striking about the objects is their materiality. What kind of materials do you use for them?

Much of the materials are industrial waste, found, such as this jacket or that mattress which I modify adding self -made materials, concrete and canvas. It is an obsession that I have. I am an opportunist; I seek, look and hunt for things within my surroundings.

It is interesting how the materials can transform and perform into something they never intended to be. It is not so much about finding something and presenting it as it is, it is not a statement. The process of finding, collecting, and scheming opportunities has equal importance to the actual making of the objects. Is more of a game for me to see what specific elements the materials can keep in combination with what I can do with them. All of these objects in the studio still need to be finished; they are still in process.

I like the roughness of them.

Yes, I like it too I am careful not to edit it too much. I don’t want to improve the works into perfection or make them decorative. I like that they are raw in their expression, even to the point of being ugly.

This year I also started to work with concrete for the first time which is quite difficult, as you must be very precise.

Do these works also have a political claim?

Apart from that they all relate to the fractured body residing in a mode of transition, it is also ironic that, on the one hand, I am working with waste material, litter, and scrap directly from the streets, on the other,

combining that with this classical oil painting. So, yes, I guess it becomes a mirror of neo-capitalism.

What are the plans for the next weeks and months to come?

I want to finish and work on the objects here and find ways of experimenting with how it could be presented and documented. And, of course, I am also always painting. So, basically, I am just continuing with what I am doing already. There will not be any new projects until I have finished these works.

I-CHING

PAST:

The woman who killed the dragon, the creature invented by human mind.

PRESENT:

Balance

WHAT NEVER LEAVES ME:

The Magician

NATURE:

The woman who spread the jaw of the lion.

DRIVEN BY:

Phoenix

WHAT I WILL LEAVE BEHIND:

Art.

Never underestimate a certain regenerative development deriving from the myth.